Shogatsu

Celebrating the New Year in Japan

Shogatsu (正月) is the Japanese New Year and one of the most important annual celebrations in Japan. Since Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873, Shogatsu has been observed on the 1st of January. Celebrations traditionally last several days from the 1st until the 3rd or 4th of January, a time when businesses close and people visit families to celebrate. Rather than a single night of celebration, Shogatsu is a ritual season focused on purification, renewal, and the symbolic break between years, offering the chance of a completely fresh beginning. In this post I’ll give a brief introduction to some of the traditions associated with Shogatsu. Many customs centre around preparing both the home and spirit to receive Toshigami, the new year kami, believed to bring good fortune, health, and prosperity. I will also include my usual selection of Japanese woodblock prints related to Shogatsu, as well as a couple of new year yokai that you might want to watch out for.

Osoji - The Great Clean

Before the New Year arrives, the old year must be cleared away. Traditionally, susuharai (煤払い) was an end-of-year ritual cleaning ceremony in which priests and households removed soot, dust, and grime from tatami mats, ceilings, and household objects. This physical act of cleaning was also a spiritual purification intended to remove the stains and baggage of the previous year. While the ritual still occurs in shrines, the practice has evolved into osoji (大掃除), literally ‘big cleaning,’ which is carried out in the final days of December. It is said that a clean home allows the visiting deity Toshigami (the year god) to enter unimpeded by physical or spiritual clutter, and for the household to cross into the new year unburdened. There is also a belief that all tasks and duties should be completed before the end of the year. Many workplaces will hold bonenkai (year forgetting) parties to help let go of the old year ready to welcome the new.

Shogatsu Decorations

After cleaning the home, new year decorations are put up. Kadomatsu are arrangements of pine and bamboo placed at entrances, symbolising longevity (pine) and resilience and growth (bamboo). Kagami mochi is another decoration that also serves as a vessel for Toshigami to reside in during Shogatsu. The word kagami means mirror and this is connected to ancient sacred mirrors. The mochi (rice cakes) represent the ending and coming years (or the sun and moon) and the bitter orange on top represents generational prosperity. They are typically eaten early in the new year.

Eating Long Noodles – Toshikoshi Soba

On Omisoka (New Year’s Eve) many households eat toshikoshi soba (buckwheat noodles). Long noodles represent a wish for long life, while the fact that soba breaks easily symbolises the cutting away of misfortune from the old year. Buckwheat is also a hardy plant, associated with resilience and endurance. Traditionally, the noodles should be finished before midnight, as leaving them uneaten risks carrying misfortune into the New Year. Another special dish eaten at new year is osechi ryori, which are special bento-like boxes including a selection of items that are symbolic of good fortune for the year ahead.

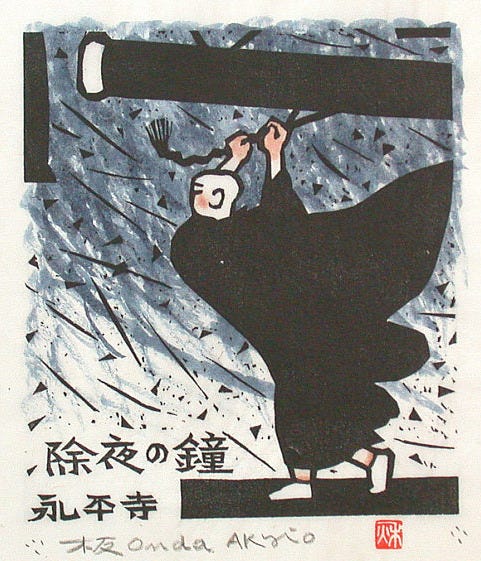

Joya no Kane – Midnight Bells

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, Buddhist temples perform Joya no Kane, ringing their bells 108 times. Each toll represents one of the 108 earthly desires or attachments believed to bind humans to suffering. With each ring, one of these burdens is symbolically released, allowing people to enter the New Year with a cleansed spirit and a calmer mind. By the final bell, the old year, and its accumulated weight, is left behind allowing for a spiritual reset.

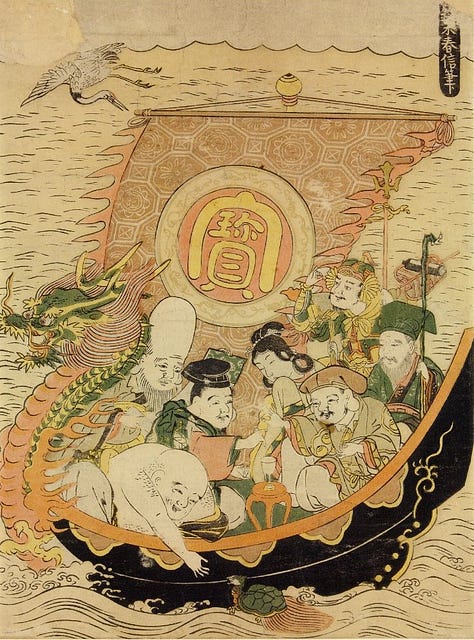

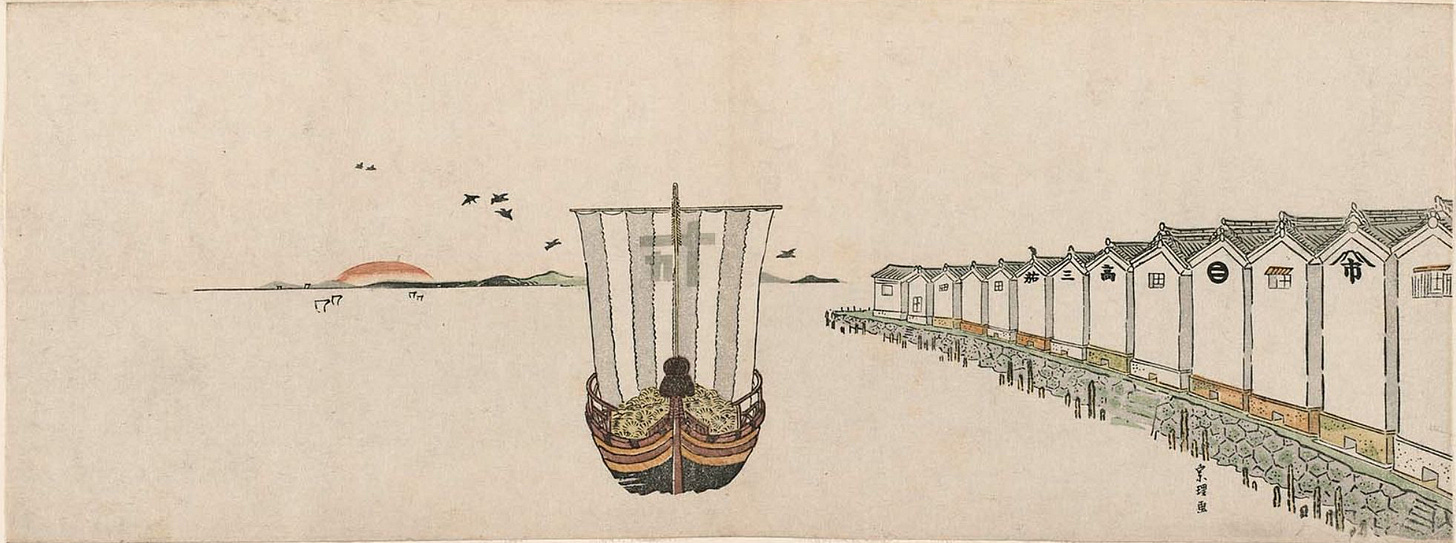

The Seven Lucky Gods and the Takarabune

Japanese folklore tells of the Seven Lucky Gods (Shichifukujin) who travel together each New Year aboard a magical treasure ship known as the Takarabune. They are believed to sail from heaven to the human world, distributing luck, prosperity, and happiness to those who have lived well. The gods carry sacred treasures associated with wealth, longevity, wisdom, and protection.

One custom involves placing a woodblock print of the Takarabune under your pillow on the night of the 2nd of January. Having a lucky dream is taken as a sign of good fortune to come, while a bad dream means the image should be cast into a river to carry misfortune away. The seven gods in their treasure ship was a common theme in ukiyo-e art and I’ve included a gallery of examples below. Perhaps you might like to print one out to put under your pillow this new year.

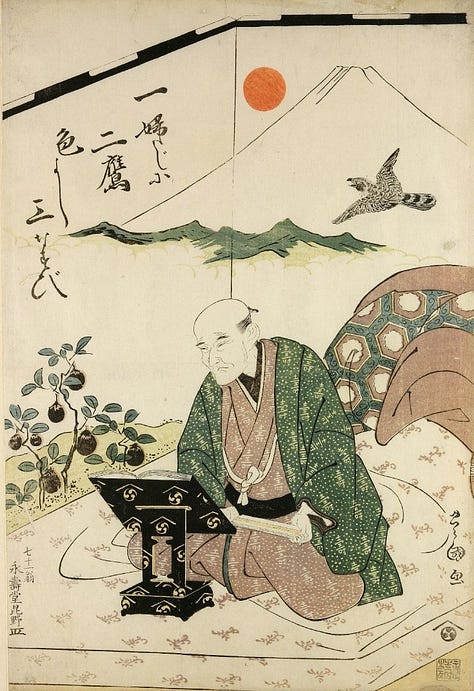

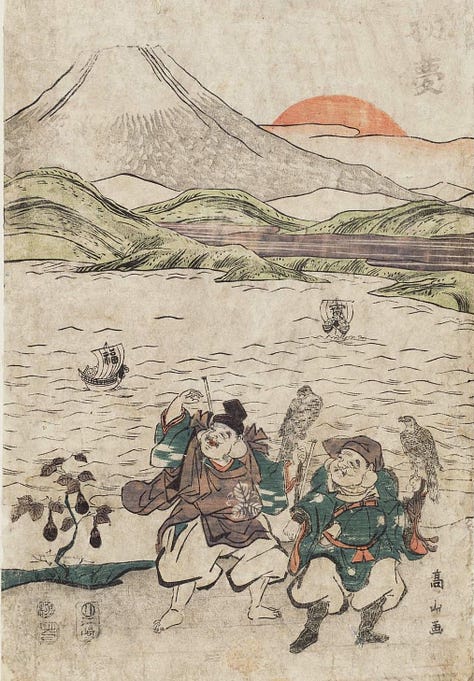

Hatsuyume – The First Dream of the New Year

Hatsuyume is the first dream of the New Year which is believed to foretell the year ahead. The most auspicious symbols to appear in this dream are Mount Fuji, a falcon, and an eggplant. Seeing any (or all) of these is considered a sign of great luck as they are said to represent safety, strength and achievement. This belief connects closely with the Takarabune tradition, reinforcing the idea that dreams during the New Year can provide insights about the fortunes of the year ahead. The three prints below are all examples that include these three lucky symbols.

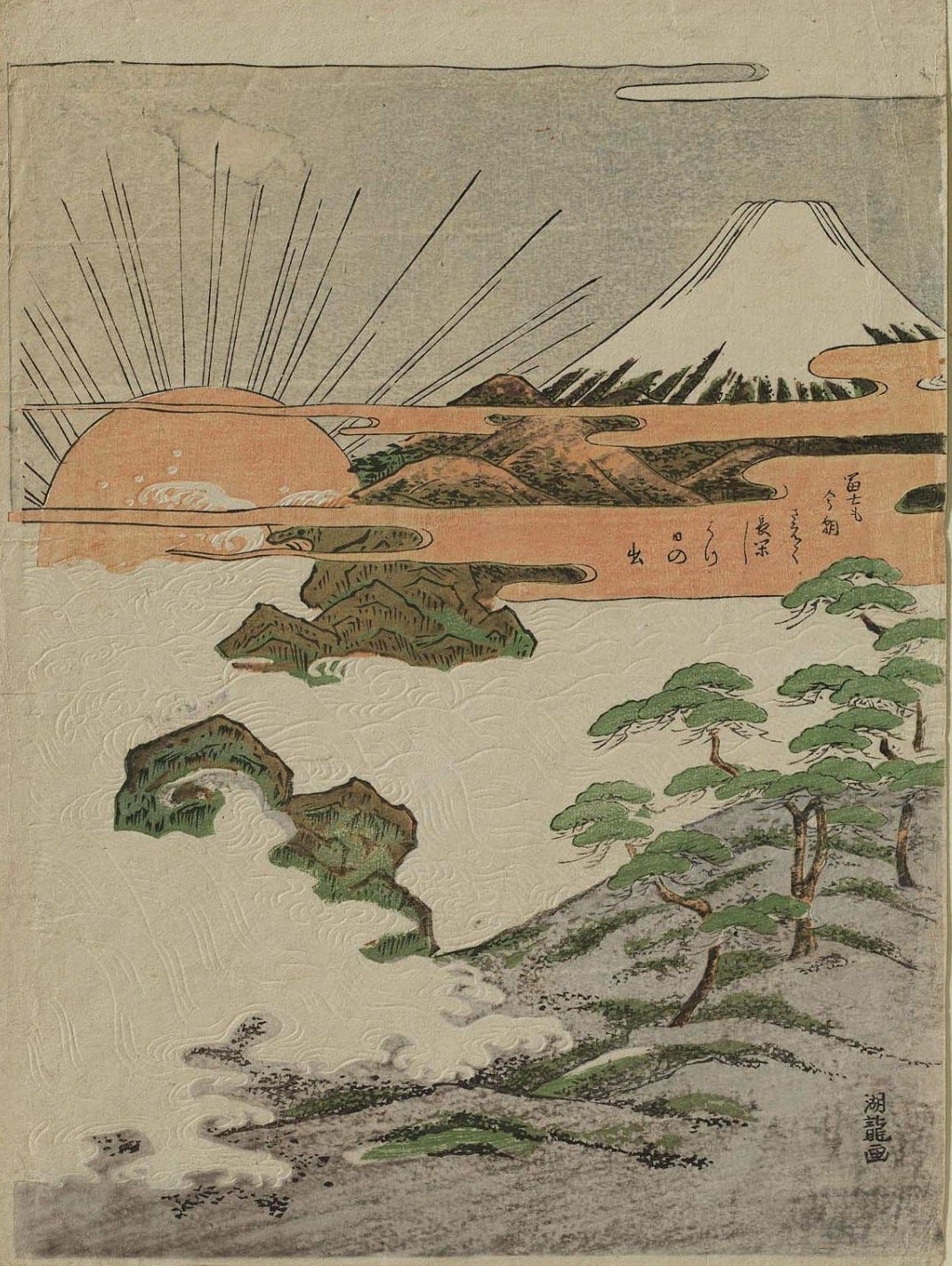

Hatsuhinode – The First Sunrise

Many people like to watch the first sunrise of the new year, known as hatsuhinode. Viewed from beaches, mountaintops, or other high vantage points, the rising sun is believed to set the tone for the year ahead. Hatsuhinode is considered a liminal moment, when the boundary between the old year and the new fully dissolves. The tradition is also connected to the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu, whose return of light symbolises renewal after darkness. The day itself is meant to be calm and joyful, free of work, anger, and disorder. This is because it is believed that the manner in which the year begins will influence the months that follow.

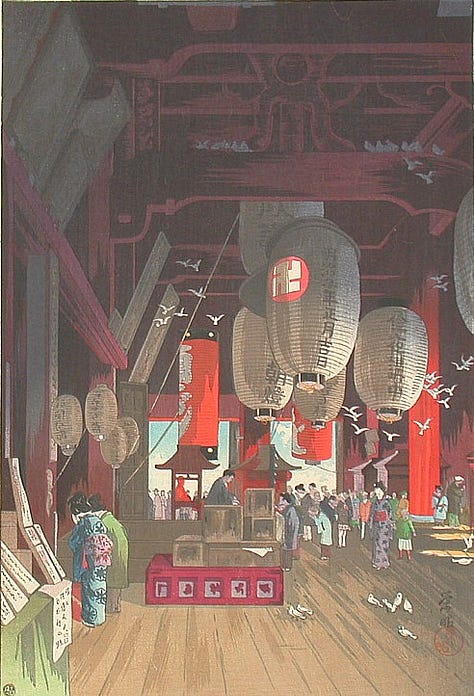

Hatsumode – The First Shrine or Temple Visit

Hatsumode is the first shrine or temple visit of the New Year. During these visits, people pray for health, prosperity, and protection, draw omikuji (fortune slips), purchase new omamori charms or hamaya arrows, and return old charms to be ritually burned. Some people also visit shrines on New Year’s Eve to participate in Toshikoshi no Oharae, which is a purification ritual. It involves a paper cut-out in the shape of a person (hitogata) which is used to absorb impurities or bad luck. The ritual allows participants to welcome Toshigami with a pure spirit.

New Year Cards and Money Envelopes

During Shogatsu, nengajo (New Year cards) are sent to friends, family, and colleagues to convey good wishes for the coming year. They are often delivered precisely on the 1st of January, but are traditionally withheld if a death has occurred in the family that year. Otoshidama refers to money given to children in small decorative envelopes called pochibukuro. They often feature auspicious imagery, such as zodiac animals or gods of fortune, reinforcing that the gift carries symbolic luck as well as money.

New Year Yokai

Namahage

In northern regions of Japan, particularly Akita, Namahage appear on New Year’s Eve. They appear as fearsome ogre-like figures and visit homes, demanding to know whether children have been lazy, disobedient, or unkind. Despite their shouting voices and frightening appearance, Namahage are not actually malevolent. They function as moral enforcers and bringers of good fortune, and families normally offer the them food and sake while they are being interrogated.

Kanbari Nyudo

Kanbari Nyudo is a fairly obscure yokai believed to appear near toilets on New Year’s Eve. Often described as a hairy, monk-like figure, peeking in while people use the toilet. Varying stories have him blowing a cuckoo out of his mouth, or attempting to lick the person using the toilet. Either way, his appearance is believed to be a sign of back luck to come. According to yokai expert Matthew Meyer, if you enter a toilet on New Year’s Eve you should chant the phrase ‘ganbari nyudo, hototogisu’ (ganbari priest, cuckoo) in order to keep this yokai away.

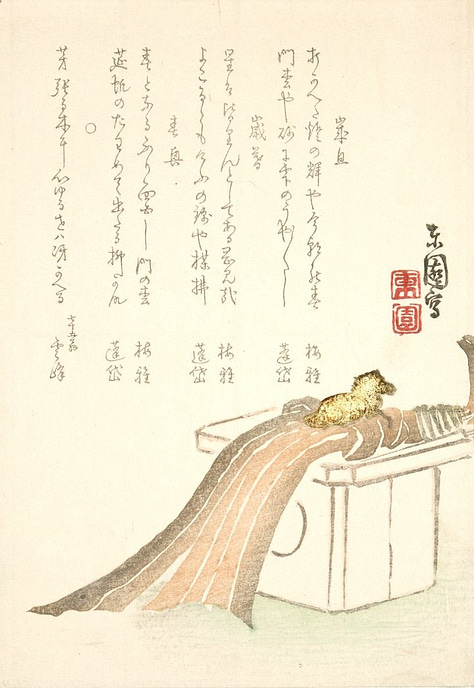

Shogatsu in Japanese Woodblock Prints

Surimono are a genre of woodblock prints from the late 18th to mid 19th centuries. They were privately commissioned, high quality prints that contained symbolic imagery along with poetry or literary allusions. In some cases they also used techniques such as embossing (see below) and metalic inks. Some of the prints so far in this article have been surimono that would have been exchanged on special occasions like Shogatsu.

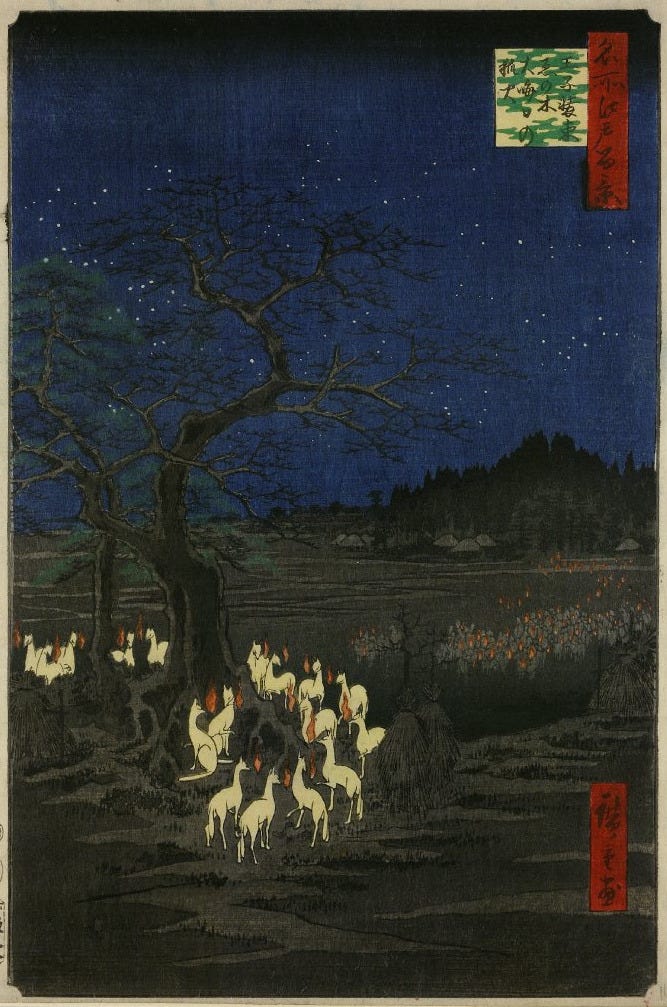

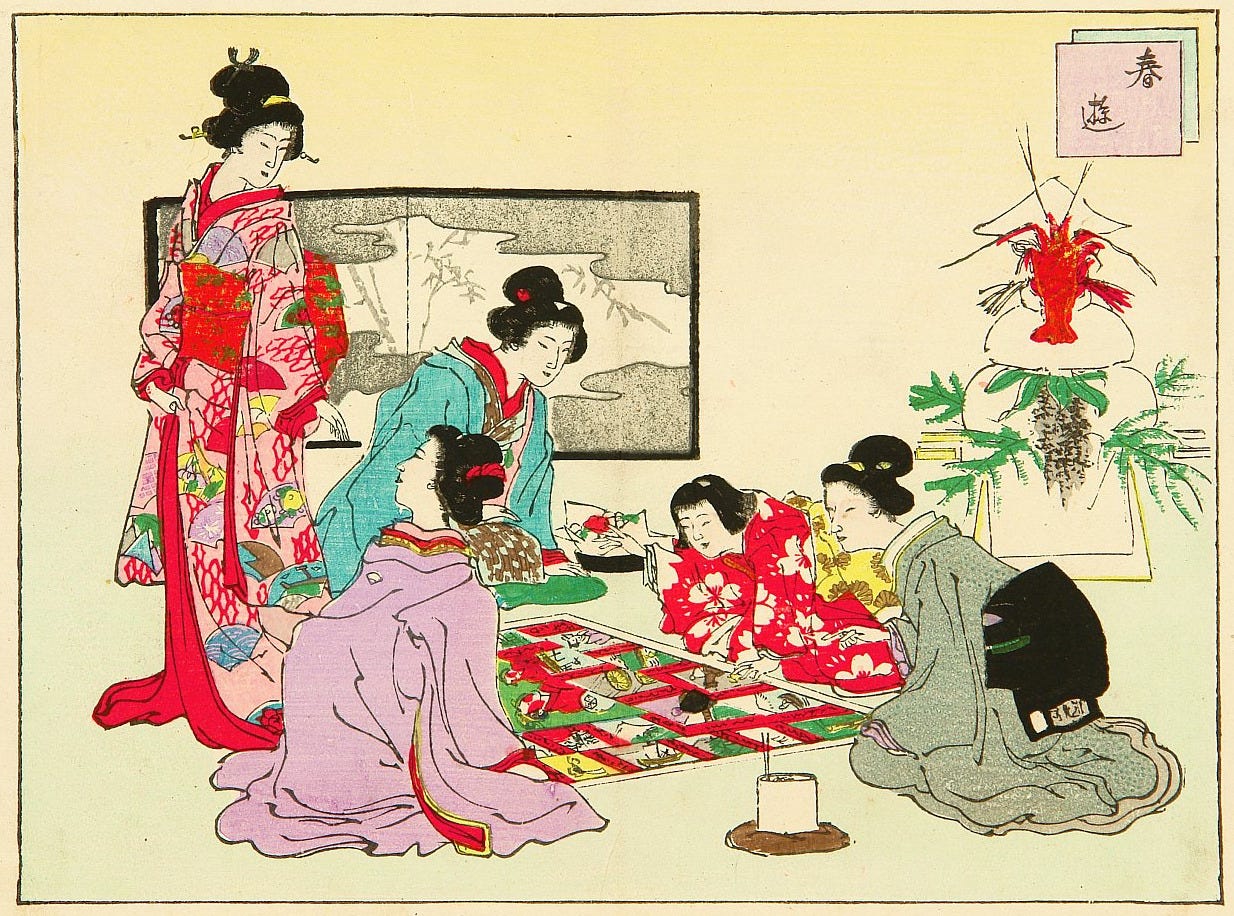

Ukiyo-e prints were mass produced for the general public, but in my opinion they were no less beautiful. Utagawa Hiroshige’s iconic ukiyo-e print below depicts magical yokai kitsune (foxes) visiting the shrine on New Year’s Eve. In Japanese folklore, apparently all the foxes in the Kanto region would visit the Inari Shrine of Oji to pay respects and get instructions for the coming year.

Ukiyo-e prints often depicted everyday scenes like this family enjoying time together on New Year’s Day.

The Seven Lucky Gods were a very popular subject for ukiyo-e prints and there were many variations on the theme. The humorous print below shows three of the lucky gods (Ebisu, Daikukoten and Benzaiten) having a picnic as the treasure boat arrives to collect them at new year.

The prints below take another approach. The first depicts a woman watching two boys towing a wagon in which a model takarabune treasure ship can be seen. The second print shows three young boys pretending to be the takarabune of the Seven Lucky Gods.

Katsushika Hokusai may be famous for his great wave, but the print below is also one of my favourites. It shows two figures as spirits of the pine trees greeting the rising sun on New Year’s morning. Just looking at it give me a sense of the possibilities that come with a new beginning and a fresh start.

Year of the Horse

2026 is the Year of the Horse. Many of the money envelopes (pochibukuro) gifted to children have the sign of the zodiac for the year ahead. So what can we expect from a Horse year? Apparently the horse symbolises strength, vitality, freedom and success so it’s a year for action, personal growth, and embracing new challenges. It seems this could be a year of breakthroughs, opportunities, forward momentum, and good luck. I’m starting to feel excited!

This has been a very brief overview of Shogatsu but I hope it has given you a sense of how the new year is celebrated in Japan. It is nearly a year since I began publishing on Substack and I want to say a huge thank you to everyone who has read my work and supported me along the way. I sincerely hope you have enjoyed the things I have shared and I would like to take this opportunity to wish everyone a wonderful Shogatsu. May the new year bring you happiness, good health, and exciting opportunities. This newsletter is completely free but if you would like to support my work, donations will be most gratefully received via Ko-fi.

Yoi Otoshi wo Omukae Kudasai

良いお年をお迎えください

Happy New Year

Have a happy new year 😊

Great work, happy new year