Tanabata

The Japanese Star Festival

On the 7th of July each year people in Japan celebrate Tanabata (七夕), also known as the star festival (星祭り, Hoshi Matsuri). This summer celebration is based on a Chinese folktale about two estranged lovers and it was brought to Japan over one thousand years ago. In this post, I’ll briefly explore the history of Tanabata, the folktale that inspired it, how it is celebrated today, and some examples of Japanese woodblock art depicting the festival and its celebrations.

The Tale of Orihime and Hikoboshi

Long ago a beautiful princess named Orihime lived in the heavens. She was the daughter of Tentei, the Heavenly Emperor and wove exquisite garments for the gods using threads made of starlight. It was said that her cloth was so fine and delicate that even the stars admired it. She worked at her weaving beside the banks of the Amanogawa (River of Heaven), which we know as the Milky Way.

Even though everyone loved Orihime’s work and she brought such great joy to her father, she felt very lonely. Tentei notice how sad his daughter seemed and so introduced her to a young cowherd named Hikoboshi who lived on the other side of the Amanogawa. He was a hardworking man who tended to the herd of celestial oxen. When Orihime and Hikoboshi met, they instantly fell in love and married soon after.

Unfortunately their happiness didn’t last. They were so enamoured with each other that Orihime neglected her weaving and Hikoboshi allowed his oxen to wander aimlessly across the skies. The heavens began to fall into disarray and Tentei was furious. He forbade them to see each other and sent them back to their opposite sides of the Milky Way.

Orihime was utterly heartbroken. She wept and pleaded with her father to allow them to see each other again. Tentei felt sorry for her sadness and agreed they could meet, but on one condition: they could see each other just once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, only if they fulfilled their responsibilities during the rest of the year.

It is said that the first time they tried to meet they could not cross the river to see each other. Orihime cried so much that a flock of magpies arrived to form a bridge with their wings so the lovers could meet. Every year on this special night, the stars Vega (representing Orihime) and Altair (representing Hikoboshi) move closest together in the sky.

History and Traditions

Tanabata (七夕) translates as ‘Evening of the Seventh’ and is based on the Chinese Qixi (double seven) festival which was held each year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. In around 755 C.E. the Empress Koken adopted the Chinese festival which became popular with the Heian court. Over time it evolved and became Tanabata. The original festival involved priestesses weaving sacred cloth on a loom, which was also called a tanabata, and offering prayers so that the gods would protect the autumn harvest. Tanabata became popular among the general public in Edo times and was often combined with the Obon festivities. After the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in Japan, the Tanabata festival was moved to the 7th of July and Obon to the 15th of August.

During the Tanabata festival the tradition is to write wishes on strips of coloured paper which are called tanzaku and hang them from bamboo branches. In past times the wishes were written as poems and girls wished for improved sewing skills while boys for better handwriting. Thankfully today, people can wish for whatever they desire. During the festival other decorations can be seen hanging from bamboo including orizuru (origami cranes) to represent good health and longevity, kinchaku (origami purses) to represent financial success, and fukinagashi (paper streamers representing Orihime’s weaving threads). Afterwards the decorations are taken down and placed in a river to float away and symbolically travel to the stars where the wishes can be granted. Alternatively, and more commonly today, they are burned.

The weather on Tanabata is very important. If the sky is clear, it is believed that the magpies have formed their bridge so the lovers can be reunited. But if it rains, Orihime and Hikoboshi will need to wait another year to see each other, and the rain is said to contain their tears.

I discovered that there is also a traditional Tanabata song and the translation below is courtesy of the Japanese Language and Culture Network at MIT (via Wikipedia).

The bamboo leaves rustle,

And sway under the eaves.

The stars twinkle

Like gold and silver grains of sand.

The five-color paper strips

I have written them.

The stars twinkle,

Watching from above.

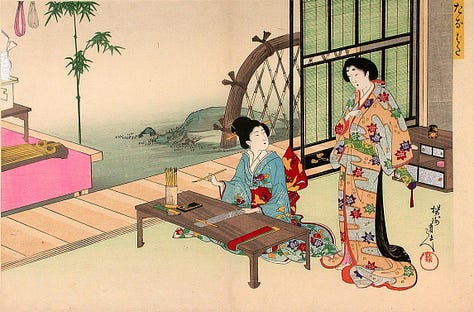

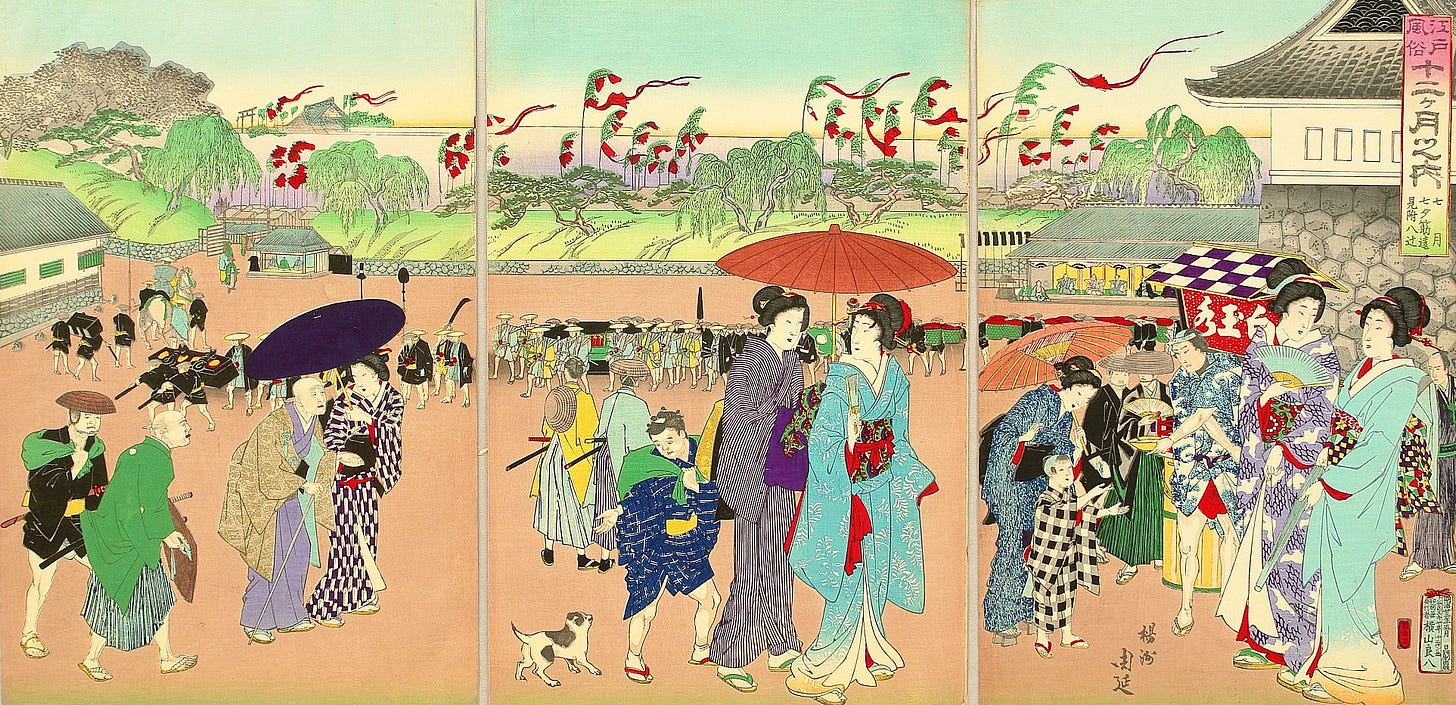

Tanabata in Art

As with many Japanese festivals, Tanabata has inspired countless examples of art and poetry. The tale of Orihime and Hikoboshi is a popular subject in woodblock prints, haiku, and even Noh theatre. I have included below a selection of woodblock prints featuring Tanabata celebrations.

Matsuo Basho, the great Edo-period poet, captures the sadness of a rainy Tanabata in this haiku:

At Tanabata

The herdsmen can’t meet —

Rain in heaven

I believe today in Japan is predicted to be very hot and sunny but lets hope for a clear sky tonight so the lovers can be reunited. May everyone’s Tanabata wishes come true.

This newsletter is completely free. If you enjoyed this article and would like to support my work, donations will be most gratefully received via Ko-fi.

Gorgeous pictures!